With more than half of the world’s population living in cities – and more moving in every day – urban mobility services are struggling to keep up. Bursting at the seams in terms of population growth, city councils are having to deal with citizens’ growing demands for more efficient, cheaper and easier-to-use transport options. In the era of global austerity and ever-siloed local authorities, it is no surprise that city governments are in many places being bypassed by emerging tech startups who can offer their end-users – the traveling urban public – the mobility solutions that they want. Think Citymapper, the international multimodal travel app, Drivy, the new Spanish car-sharing service, or Ofo, the app that lets you hop on a bike anywhere in the city.

A Not - So - Smart City

The only problem with all this innovation is its unforeseen consequences, as Atlanta, Nashville and San Francisco recently realized when the startup, Bird, unleashed its electric scooters all over their cities. While Bird’s nifty little scooters undoubtedly help citizens to quickly travel short distances – solving the last-mile problem – they also block pavements and pose a safety risk when people break the rules and ride them in prohibited areas. Many Chinese cities, such as Shanghai, also began to face a similar problem when dozens of bike sharing companies flooded city streets with millions of rental bicycles last year. The urban infrastructure was not prepared to handle this amount of oversupply – resulting in massive piles of broken, abandoned bikes laying around in the streets – and public services were also slow to tackle the situation. The bike-sharing boom didn’t seem quite so exciting anymore when whole fields outside Shanghai were filled as far as the eye could see with bikes.

Bird and other mobility companies’ take-over of many cities is bad news for city councils because of its effect on citizen satisfaction levels. At the end of the day, it is the city governments who are seen as responsible for dealing with the problems caused by these new tech disruptors. So if a citizen is peeved about the scooter parked on his driveway, he will ultimately blame the council for not doing anything about it. Vandalism is also an issue – for example, Chinese company, Mobike, recently threatened to remove its bikes from Manchester, UK due to so many of them being vandalized or abandoned. Dealing with this vandalism again falls into the hands of the local authority, who are the ones providing the public security services – such as the police – in their local area.

Local authorities are therefore realizing that they urgently need to intervene in the growing mobility marketplace in order to make sure that the new technologies being implemented in their cities are actually beneficial to their citizens – for their own sake as much as the people’s.

From regulating to banning

Many authorities are looking to solve the issues caused by new mobility technologies by regulating – or even simply banning – them. The Bird saga offers us plenty of material here. From San Francisco, to Santa Monica, to Tennessee, city councils are putting in place measures to make sure that Bird’s little scooters don’t become a large problem in their city. Santa Monica, where the company is based, sued Bird before reaching a settlement that allowed it to operate, Bloomberg reported. The company similarly received a ‘cease and desist’ letter from Nashville metropolitan authority in May 2018 after only two days of being in the city. The company was told they had 15 days to remove the scooters or the local authority would do it instead.

Bird is not the only disruptive mobility startup facing opposition from local and national governments. Uber is a prime example of a disintermediating mobility disrupter which has faced a lot of public – and in turn governmental – backlash. Uber has already actively been banned from some of the world’s cities – Barcelona and London are examples of this. Uber’s continuing lawsuits with more than a handful of the world’s cities are the testament to how cities are trying to regain control of the transportation situation in their city, cracking the whip with those companies who are perceived to be ‘too disruptive’ to allow.

Finding a middle-ground

Questions remain over whether regulation is effective, or even desirable. These new startups are, after all, only responding to the law of supply and demand. Many also argue that regulation of any kind stifles innovation, stopping nascent companies from realizing their potential.

A Startup Mentality in Palo Alto

Some city councils are taking an alternative approach to innovation in the mobility space, either alongside or instead of regulation. Palo Alto, the famous birthplace of Facebook in Silicon Valley, have decided to take on a ‘startup mentality’, working with local and international tech disruptors to test out new mobility solutions – such as autonomous cars and robots – on the city’s streets. In 2016, the city council decided to make itself a ‘testing area’ for driverless vehicles, and they are now a fairly regular sight on their streets. In fact in the state of California in general, there are now 27 companies that have permits to test autonomous cars on real streets, with a total of 180 vehicles approved for operation.

Approaches for cities to take back control

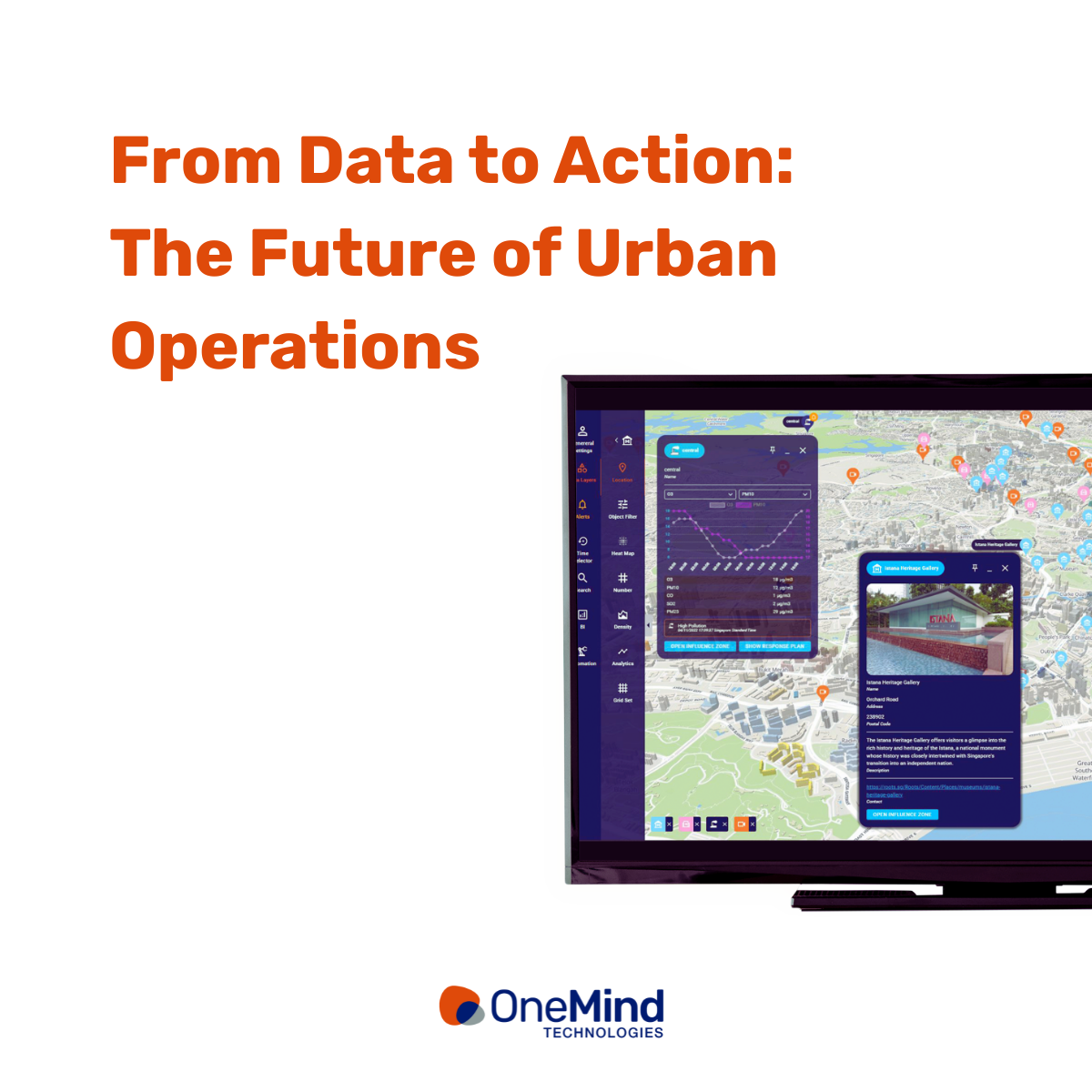

A crucial tool for city councils looking to gain more or regaining control of their city’s mobility operations is an overarching mobility or global city operations solution – such as an operational intelligence solution for city control rooms. These IoT based solutions are comprised of a smart core platform which allows integrating any existing city IT system e.g. for smart waste management, or data sources like smart sensors. Local transport officials can oversee and manage all of the city’s transport in one place through digitizing mobility ‘assets’ – moving or static – so that they can be monitored in real-time: traffic lights, CCTV cameras, parking spaces, police officers, smart bike or scooter locks, among others, are connected through an advanced, long-range, IoT network and transmit their data to a gateway which communicates with a software application that interprets the data sent into useful, actionable insights to help city operators make data-driven decisions.

Eradicate internal silos

An intelligent city mobility solution enables local councils not only to eradicate internal silos, because cross-departmental collaboration is easier when everyone is using the same technology but also to work more cooperatively with external mobility – and other sectors – stakeholders, including the market disruptors. With the aid of an overarching city operations management system, city operators can, for instance, see where all ‘connected cars’ are in the city and therefore manage congestion by implementing measures to redirect traffic or change traffic-light sequencing.

Sharing third-party data with cities

IoT solutions are becoming more and more essential when it comes to urban disruptors – particularly those in the sharing-economy space. Imagine that through their smart locks every bike or electric scooter is transmitting real-time information about its status and location to a central transport hub where the IoT solution is doing its thing, and every person in the city is using a mobile application to locate and book these shared vehicles. City-councils can then effectively oversee and integrate the supply and demand of these disruptive mobility options in their overall mobility strategy, making sure that public and private transport is not only more resource-efficient and functional, but, as a result, quicker and easier to use for city-dwellers.

The challenge cities are facing here, is to come to an agreement with third-party providers to share the data of their vehicles – generate through smart locks – with the city council.

By investing in a comprehensive operations management system, cities will be able to incentivize third-party providers to share their data through, for instance, giving them access to new city populations and therefore new markets through end-user applications like smart parking or multimodal mobility apps. This data can then, together with all existing city data, be integrated into a “system of systems”, through which urban mobility, as one aspect of the system, can be managed holistically, strategically and collaboratively. This benefits cities, allowing them to regain control, and also mobility providers, enabling them to cut idle-time and increase their turnover.

A combined approach

Every city is different and will deal with mobility disruption in its own way. A combined approach – a little regulation here, a little experimentation there, in addition to introducing a holistic city management system – looks like it will be the way forward. Cities need to stay on top of emerging mobility trends – both locally and internationally – and make sure that they are collaborating with all stakeholders across the city community. This is where IoT mobility management systems are essential. Digitization generally redefines the value chain, putting customers/citizens at the center; it also massively facilitates cooperation and collaboration. This is what urban mobility needs right now – a redefinition according to actual citizens’ needs, and then the tools to facilitate collaboration and innovation.

Third party mobility providers are often operating in an ‘a-legal bubble’ due to the lack and slowness of regulations being put into place. The question remains, how can local authorities participate in or even lead urban transport innovation in a digitized world? How can they influence new city mobility operations?

Aside from putting in place regulations, cities need to experiment themselves – as Palo Alto demonstrates. This requires not only qualitative engagement with citizens but also the collection of quantitative data through city mobility systems. Ultimately having data on how citizens actually use transport options in their city and what they want out of transport will allow public authorities to develop solutions in collaboration with other public-sector and private-sector stakeholders that are more effective and relevant to citizens’ needs, making for ‘happier cities’ in the long-run.